Von Pfister general store placed on National Register

by Donna Beth Weilenman

One of city’s first buildings earns long-sought designation

For decades, those interested in Benicia history have told the story of how Charles Bennett stopped at Edward Von Pfister’s general store in 1848 and announced that gold had been found at the mill site of his employer, John Sutter. The announcement touched off what became known as the California Gold Rush.

Completed in 1847, the little adobe building where Bennett made his proclamation is one of Benicia’s first buildings. Now it’s on the National Register of Historic Places, said Jerry Hayes, former mayor and president of the Benicia Historical Society.

Hayes said the designation has been the group’s goal since soon after its founding in 1973.

“We’ve been trying for years,” he said, saying the task has been undertaken by first one person, then another. From time to time, society members wondered if the designation would ever be achieved: “We had so many false starts.”

By the time Hayes was Benicia’s mayor, in the 1990s, the society asked for the city government’s support, and Hayes readily gave the quest his endorsement.

After his time as mayor, the historical society still had not accomplished its goal of getting the old adobe building on the historical register. Hayes realized the group needed money to get the documentation and complete the forms that would earn the old general store national recognition.

Hayes said he knew that “if we are going to get anything accomplished, we need revenue,” so when some society members wanted the organization to drop its tour of local historic homes, he pressed not only to keep the fundraising event but to make it more appealing.

But the society didn’t stop there. Members approached the City Council and asked for help in paying for a consultant to write the application. The city picked up half the $13,000 tab.

The society hired a firm that had researched the Presidio and the Commanding Officer’s Quarters. But once again, it ran into a brick wall: The consultant urged the society to seek “archeological ruin” designation of the old adobe building, which meant the building would be left as-is with no chance of any level of restoration.

A “ruin” has lost significant elements, Hayes said, and the designation reduces the recognition to that of a “site.” That means the place itself is labeled the location of a significant event, occupation or activity, even if the structure on the site has no value or is demolished.

Shocked, the group “could have asked for our money back, but that didn’t happen,” Hayes said. But neither would the society accept the consultant’s recommendation.

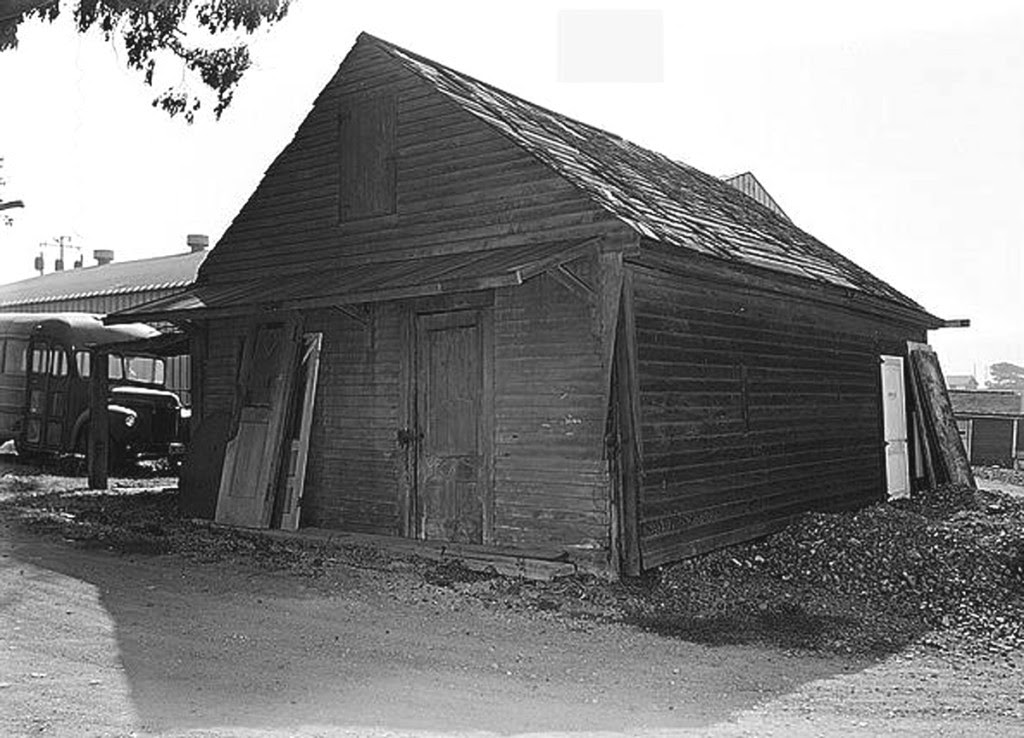

Hayes said the society’s longtime goal has been the preservation, even restoration, of the old adobe building, so it could be put back on display instead of being hidden from view on Phil Joy’s property on the south side of First Street on an alley named for Von Pfister.

So the group went back to work.

Hayes found an ally in Dr. Kerry Carney, a member of the historical society’s board. “She’s a writer and editor for the California Dental Association,” he said. “I asked, ‘Would you help me with a project?’”

The “project” — a complete rewrite of the application.

The pair kept the information they thought they needed, and stressed the importance of the old general store not only to the 1849 California Gold Rush, but its association with Von Pfister, described by Hayes as “a significant historic figure.”

Von Pfister, according to an account by Richard H. Bullock in “The Ship Brooklyn Story,” was a Boston-area native who skipped out on an apprenticeship to become a cabin boy. By 24, he was captain of his own ship and had sailed across the Atlantic Ocean 32 times.

His shipping business had given him the finances needed to try his hand at business on the West Coast, sailing as one of only two first-class passengers on the Brooklyn. He explored opportunities in Yerba Buena, now San Francisco, as well as San Jose and Monterey. California Gov. Thomas Larkin invested in Von Pfister’s Pacific trade business.

In 1847, Von Pfister went back to Yerba Buena and met Larkin’s friend, Dr. Robert Semple, who was trying to start a settlement on the Carquinez Strait he hoped would rival Yerba Buena.

Semple convinced Von Pfister to open his store in this new community, which would eventually be named “Benicia.”

Von Pfister traveled to San Francisco and to Honolulu to obtain goods — arrowroot, beads, red sashes, hides, white linen, blue dress coats, wine, brandy and the Spanish drink aguardiente — for his new store, a 40-foot-by-18-foot adobe home that became just the third building erected in Benicia.

“He knew the merchandise,” Hayes said. “He had a log of everything.”

The businessman also kept records, not only of his merchandise but also of Benicia’s pioneers, Bullock wrote.

Bullock’s account suggests Von Pfister knew of the discovery of gold on Sutter’s land, but kept quiet until Bennett — who may have gotten tipsy while drinking at the store — reacted to the announcement of coal found on Mount Diablo.

Bennett was carrying samples of Sutter’s gold to Monterey, from which Sutter had hoped to obtain title to land around his mill. According to other versions of the story, Bennett dumped the shiny contents of his bag and shouted, “That will beat your black gold!”

Later, as gold trickled into the area’s economy, miners would come to Benicia to trade for socks, hats, boots and other necessities as they traveled to San Francisco for entertainment. Eventually, Von Pfister and Sam Brannan opened a store closer to the site of the Gold Rush; but Von Pfister was shaken when one of his brothers, John, was knifed to death in front of that store. Bullock wrote that he sold his share to Brannan and returned to Benicia to operate a hotel.

He married a widow, Mary J. Hall, in 1853, Bennett wrote, and moved to a home on West J Street. He also built a home at 280 West J St., which he sold, but not before branding the beam ends with VP, for Von Pfister.

Von Pfister’s wife was the sister of Catherine Hall, who married Joseph Fischer, the Zurich businessman who moved to what is now the Fischer-Hanlon House, part of the Benicia state park that includes California’s first capitol building.

Von Pfister eventually was elected to the first Benicia City Council, and became its justice of the peace, city clerk and a member of the city’s board of trustees, during which he helped about 200 people who sought government redress to retain their homes. He died April 9, 1886, at home, and his obituary described him as a well-loved member of the community. His widow died in 1901.

In seeking National Register designation, another point Hayes and Carney made was that Von Pfister’s adobe general store also has significant architectural significance. The pair spent hours conducting specific historical research on the store owner and his ties to the Gold Rush, and ignored the former consultant’s argument that the information couldn’t be obtained because the University of California-Berkeley’s Bancroft Library had been closed when they were involved in the project.

The pair submitted the new application in 2013 — and saw it rejected.

“It’s not good enough,” Hayes recalled thinking. But the pair didn’t give up. In fact, Carney came up with a solution.

She knew a UC-Berkeley doctoral student from Benicia who was specializing in archaeology, and she asked him if he was willing to push the application through.

David Hyde accepted the challenge, and began learning from Sacramento officials what the Benicia Historical Society’s application would need for approval.

Hyde was the essential key to the society’s success with Sacramento officials, Hayes said.

“They hit it off,” he said. “He understood what they were asking for, and got it approved earlier this year.”

The society got State Historical Preservation Commission approval at its meeting in San Diego last April, and recently was notified from Washington, D.C., that Von Pfister’s general store had, indeed, been named to the National Register of Historic Places.

But the organization isn’t resting on its laurels, Hayes said. The next phase is to make the general store a showcase.

The society’s goal isn’t to let visitors wander into the store or take tours. Instead, it would be restored, redressed as a general store, using Von Pfister’s own log as a guide for stocking its shelves, and set up as a display visitors can walk up to see, Hayes said. A plaque would describe the historic building.

The society has worked with both Phil Joy, the property owner, and city officials so that a planned waterfront trail would go past the general store. The cost hasn’t been determined; in fact, Hayes said, plans haven’t been designed yet. The price tag could be as low as $50,000 or as much as $150,000.

Meanwhile, the Von Pfister general store isn’t the only project on the society’s plate. Hyde already is researching the Southern Pacific Depot, the building that houses Benicia Main Street, with hopes it, too, can get national recognition.